Unless the voting at Ethan Allen Interiors’ upcoming annual meeting—where 5.5 percent holder Sandell Asset Management has nominated six candidates to the seven-member board—produces a landslide management victory, shareholders may be about to witness firsthand how a poorly designed majority voting standard can be used to entrench a board rather than increase its accountability.

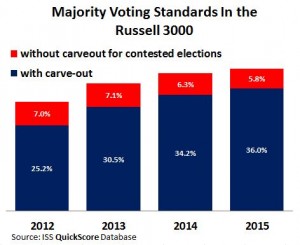

Across the Russell 3000 universe, ISS’ QuickScore shows, approximately  42 percent of companies now require that directors win a majority of shares cast in order to be elected. In a contested election, however, ballot dynamics alone may mean that some or all of the nominees getting the highest shareholder support may still not win a majority of votes cast. Six of every seven companies with amajority vote standard—36 percent of the Russell 3000 in total—therefore include a carve-out for a plurality standard in contested elections, ensuring that the nominees with the most shareholder support will be elected.

42 percent of companies now require that directors win a majority of shares cast in order to be elected. In a contested election, however, ballot dynamics alone may mean that some or all of the nominees getting the highest shareholder support may still not win a majority of votes cast. Six of every seven companies with amajority vote standard—36 percent of the Russell 3000 in total—therefore include a carve-out for a plurality standard in contested elections, ensuring that the nominees with the most shareholder support will be elected.

Another 5.8 percent of Russell 3000 companies do not: their majority voting standard applies even in contested elections, despite the very real risk the result will be a failed election. How that failed election is resolved may actually repudiate the electoral process itself, at least with regard to those candidates who won the most votes without actually winning a majority of votes cast: often, the resolution of a failed election is left to the judgment of the very board being challenged in the proxy contest.

Ballot Dynamics

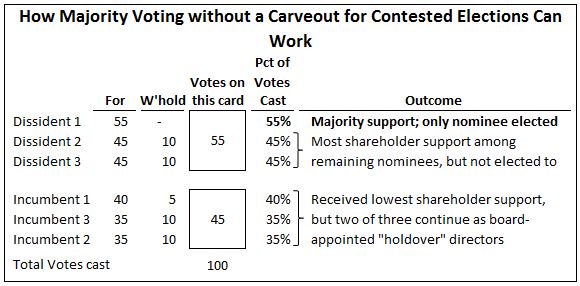

In a contested election shareholders voting by proxy must cast their vote on either the dissident or management card, but cannot generally use both. Incumbent directors who appear on both cards may (and usually do) receive a majority of votes cast.

But few, perhaps none, of the contested nominees—the dissident candidates or those incumbents they seek to replace—will. As the exhibit on the next page demonstrates, those not listed on the card selected by the majority of voters automatically fail to get majority support. Even those on the “majority” card can, with a sufficient number of withhold votes, also receive less than majority support. These latter may in fact have more total “FOR” votes than the candidates on the other card—but will still fail to be elected under the majority voting standard.

And not only, in a failed election, do all the incumbents hold over—but in an election where some seats are not filled by a nominee receiving majority support, the incumbent board itself has the ability to appoint which incumbents will holdover in those chairs, regardless of how many votes those appointees received relative to other incumbents or the dissident nominees.

Accident or Design?

Such an eventuality was, as the large percentage of companies without a carve-out might suggest, one reason some companies adopted majority voting in the first place: without the carve-out, these companies effectively raised the bar for shareholder efforts to replace directors, “protecting” the incumbent directors in precisely the situation where there was actual risk of removal.

At the same time, majority vote standards can be rendered relatively toothless in uncontested elections by not requiring directors who fail to receive majority support to resign from the board—which is the case with about one in seven majority voting bylaws. Even when director resignations are required, moreover, boards can simply choose not to accept the resignation—or, as more often happens, accept it but quickly reappoint the same director to the now-open spot. (This need not necessarily be the case, however, as Tempur Sealy’s uncontested incumbents demonstrated in May by accepting the resignations of the CEO, the Chairman, and a third long-serving director, and appointing in their stead nominees from the shareholder, H Partners, which had led the vote-no campaign.)

What Now?

The long-term question—on which Ethan Allen’s actions may have some impact—is whether shareholders will now begin to perceive ill intent, and real risk, in “shareholder friendly” governance provisions drafted in ways which can diminish, rather than improve, board accountability. –Chris Cernich, ISS Special Situations Research

Special Situations Research clients may read the full note

here